Baselitz - Naked Masters will be on view at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna from March 7 to June 25. Our special exhibition is one of the art highlights in Vienna this spring.

Kunsthistorisches Museum invited Georg Baselitz (b.1938) to take part in an exhibition project that has the artist enter into a visual dialogue with the Old Masters. He selected the works himself – seventy-five of his own creations and forty from the Picture Gallery of the Kunsthistorisches Museum –, concentrating entirely on the nude, the naked figure. The exhibition casts a light on this elementary human condition, which has always been a central topic of European art.

‘The hierarchy of above and below is in any case only a pact that we have got used to.’

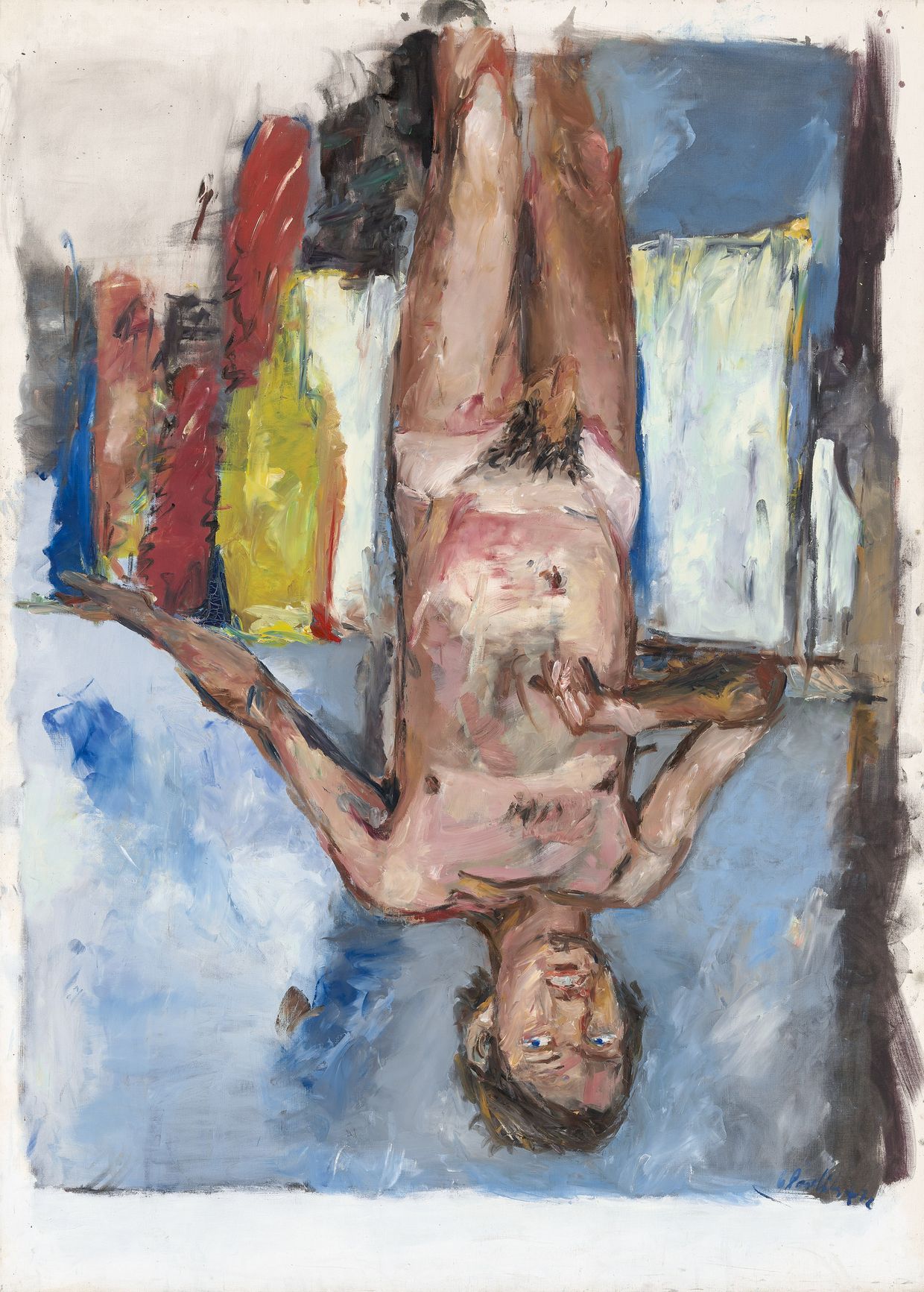

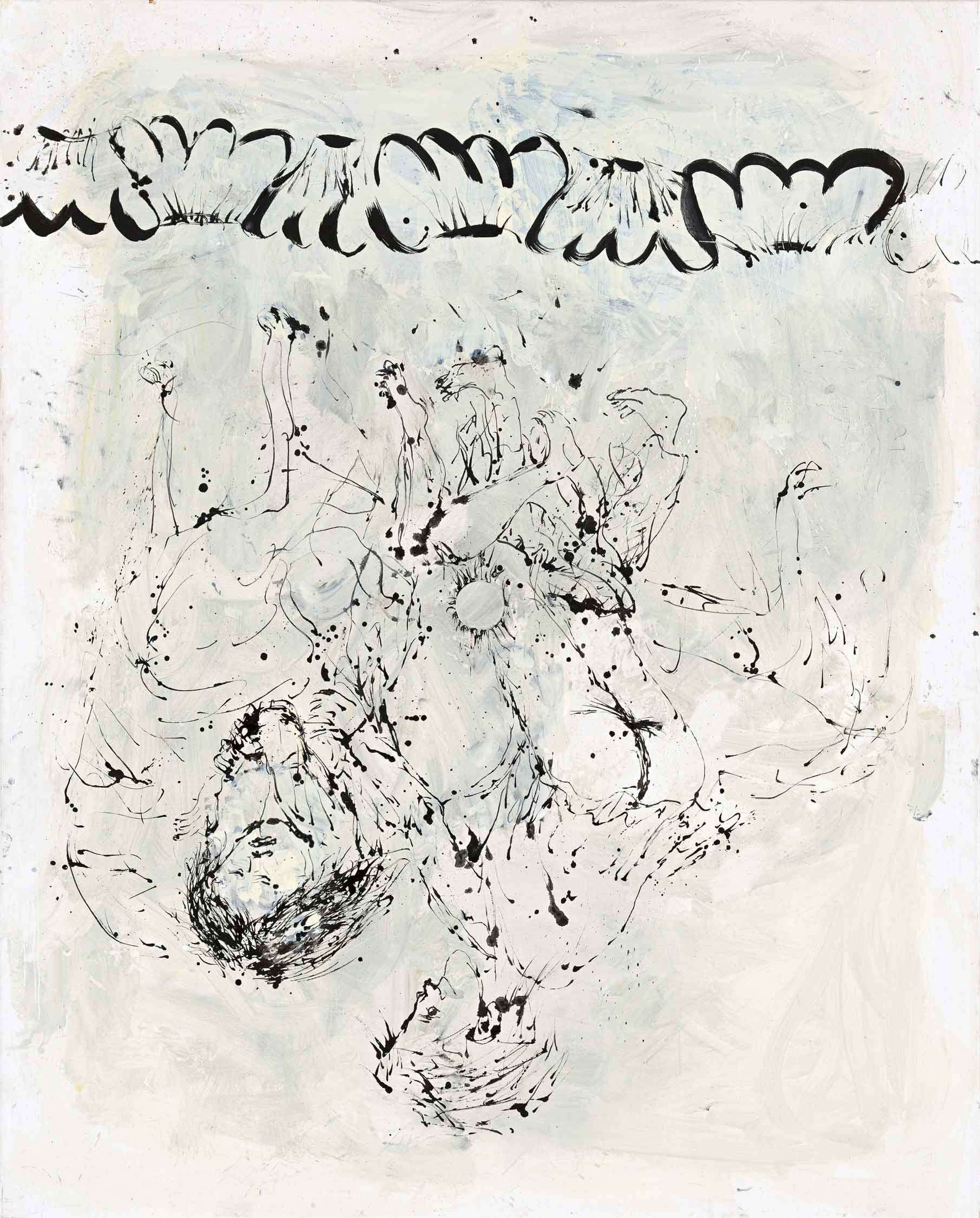

Finger Painting – Nude

‘If you want to stop constantly inventing new motifs, but still want to go on painting pictures, then turning the motif upside down is the most obvious option. The hierarchy of sky above and ground down below is in any case only a pact that we have admittedly got used to but that one absolutely doesn’t have to believe in. Ultimately, all I’m interested in is being able to go on painting pictures.’

The utter autonomy of painting manifests itself in the unauthorized, libertarian act of will that is the inversion of the motif.

Georg Baselitz, Finger Painting – Nude, 1972, Oil on canvas, 250 × 180 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

The Fall: Adam and Eve

Cranach uses subtle glances and postures to indicate that we are witnessing a significant event: inklings and processes of growing awareness of fateful entanglements. At the time, it was understood that all humans descend from this first human couple, including the painters. To formulate images of humans and reflect visually about fundamental issues is a potential that the art of painting continues to hold until this day. Not least the ability to reflect on the very medium of painting itself. This exhibition also 'speaks' of that.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Fall: Adam and Eve, 1510/20, Lime panel, 137 × 54 cm each. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, invs. 861, 861a.

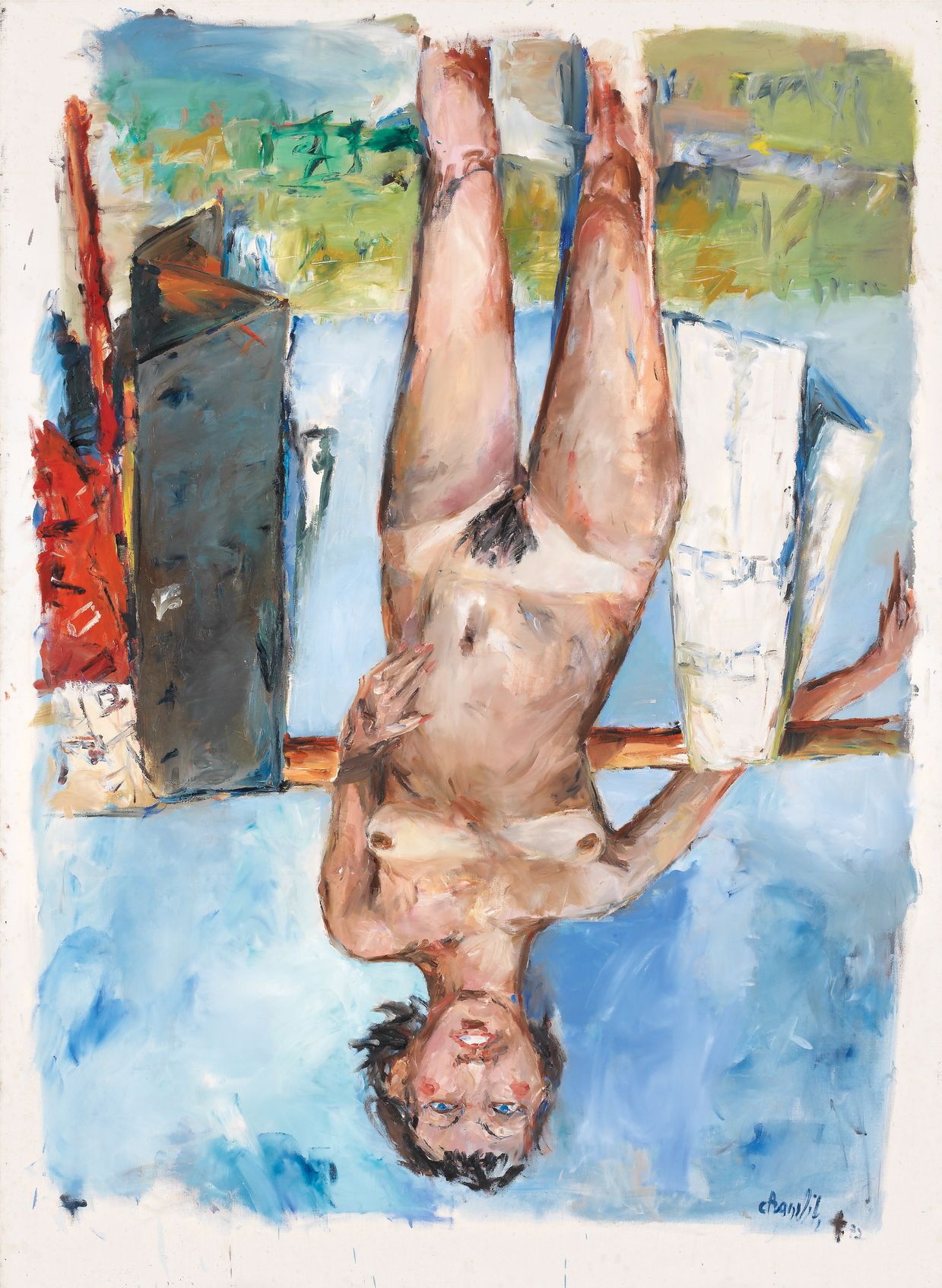

Finger Painting – Female Nude

The images on this and the facing wall were made using Polaroid photographs that Baselitz and his wife Elke had taken of each other, and which he held in his left hand as he painted. It would have been entirely inconceivable for him to have nude pictures of his wife developed in a laboratory. The pictures are not painted by brush, but with his fingers. ‘What I want to avoid, by this means, is that my paintings become a form of handwriting. (…) That was the method for one series of paintings, but then that was it, no more.’

Georg Baselitz, Finger Painting – Female Nude, 1972, Oil on canvas, 250 × 180 cm, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Donation: Georg Baselitz. © Georg Baselitz 2023

‘A painter who paints painting.’

Manisha Jothady, Wiener Zeitung, 24 January 2013

Finger Painting – Black Elke

Here, Baselitz transfers his childhood desire for dark skin to his wife. This declaration of love, expressed with tenderness and great freedom, is an event of colour and composition. The background grey and that of the bust are subtly different and animated. The white background area surrounds the bust at the upper edge of the picture, too, so that it appears as if from nowhere. At the bottom left, the picture’s shades of colour return in the form of a non-representational still-life: both echo and source of the portrait at the same time.

Georg Baselitz, Finger Painting – Black Elke, 1973, Oil on canvas, 162 × 130 cm, Private collection. © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin.

Helena Fourment (‘Het Pelsken’)

Both pictures show the extraordinary intimacy between the painters and their wives with great immediacy. Rubens was working from within a much narrower set of conventions, of course, which he confidently stretched as far as possible. He legitimized the life-size depiction of his almost nude wife by resorting to the familiar statue type of the ancient Venus pudica. For Baselitz, Helena Fourment (‘Het Pelsken’) is ‘simply a wonderful painting. When you see a picture like that, you have to say either I never want to die or I will die happy! Those are incredible experiences.’

Peter Paul Rubens, Helena Fourment (‘Het Pelsken’), 1636/38, Oak panel, 178,7 × 86,2 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 688

Lot and His Daughters

At first sight, we seem to be looking at an ill-matched couple. It is the girl sitting before the flaming city in the background that reveals that we are facing the story of Lot and his daughters, a story that was as disquieting then as it is now. Did the artist want to refer to the egregious nature of the biblical event by using such an entirely unusual staging within the tradition of the pictorial theme? Incidentally, Baselitz is not convinced by the Altdorfer attribution, he sees a close proximity to Cranach.

Albrecht Altdorfer, Lot and His Daughters, 1537, Lime panel, 107.5 × 189.5 cm, dated on the top right on the tree trunk: 1537. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 2923

Bedroom

Here, opposite the finger paintings, Baselitz takes his pictures in a new direction: the painting is less compact, it is more open, gestural, faster. The colours form a bright chord, trickling down the canvas from runny areas. What is explosive about this painting, where it burns, rests in the way it is painted, and not, as with Lot and his daughters, in the subject of the painting.

The figures were developed by drawing; their three-dimensional quality speaks of the artist’s growing interest in sculptural issues.

Georg Baselitz, Bedroom, 1975, Oil and charcoal on canvas, 250 × 200 cm, Private collection. © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

‘Everything is a self-portrait, whether it's a tree or a nude.’

Diana & Callisto

A complex, tragic story: Callisto’s forbidden pregnancy is uncovered, Diana casts her out, the impending fate is cruel. Action and reaction, gestures and glances, cast even beyond the painting. The dramatic narrative has a recipient: we are being addressed.

Such scenes are never provided by Baselitz. These two paintings have a proximity that is founded only on their internal characteristics: the related chords of color from which they are structured and the analogous arrangement of the main characters, in whole figure with outstretched arm.

Titian and workshop, Diana and Callisto, c.1566, Canvas, 183 × 200 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 71

Titian and workshop, Diana and Callisto, c.1566, Canvas, 183 × 200 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 71

The Reading Girl

Georg Baselitz’s paintings often have an introvert, hermetic trait quite independently from the subject of the image. The girl here is so very much part of the warm, cave-like space of colour within which she is standing that it appears as if not only she is occupied by her book, but the very picture is occupied with itself. The structure of the painting is both open and precise, as concentrated as it is free.

‘Everything is a self-portrait, whether it’s a tree or a nude. Everything that you see is a reflection of yourself.’

Georg Baselitz, The Reading Girl, 1979, Oil and tempera on canvas, 330 × 250 cm, Private collection. © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

‘Most artists today paint huge formats, for different reasons: vanity, hubris, demonstration, etc. That is an opportunity that is available to a contemporary picture. In the time of the Old Masters, they didn’t have that opportunity.’

Resting Venus

Van Ravesteyn is known to have been at the Prague court of Emperor Rudolf from 1589 to 1608; he probably returned to his home in the Netherlands thereafter. The picture stands in the tradition of Venetian Venus paintings by Giorgione and Titian, but the physical sensuousness is so enhanced in Ravesteyn’s version that this might indeed be the depiction of a courtesan. That is further indicated by the existence of another version of the same model with entirely identical décor. In analogy to Baselitz’s duplicate Dürer nymph, both are brought together here.

Dirk de Quade van Ravesteyn, Resting Venus, c.1608, Oak panel, 80 × 152 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 1104.

Ade Nymphen

Ade Nymphen is a phonetic adieu to Dürer and his famed ‘AD’ monogram. Baselitz cites Dürer’s reclining female nude (1501, Albertina), a finely chiselled feather ink drawing in which Dürer presents his canonical figural scheme in a primer-like construction. Baselitz liberates Dürer’s ‘nymph’ from her rigid corset, gives her fluidity and duplicates her and then colours the pair of women thus created sensuously.

‘Germans in general, and I in particular, need to have a reason for everything we do.’

Georg Baselitz, Ade Nymphen, 1998, Pencil and oil on canvas, 209 × 162.5 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Resting Venus

In 1809, Napoleon had this picture brought from the Viennese collection to the Louvre, from where it was dispatched to Dijon in 1812. In this version, the beauty turns her uncovered torso towards us in the very centre of the picture, her face is cast away. In the other version, it is the other way around. Anyone open to exploring this outrageously subtle interchange of poses cannot escape voyeurism. If the panels were placed free-standing back to back, as might be imagined, it would suggest the subject’s immediate presence.

Dirk de Quade van Ravesteyn, Resting Venus, c.1608, Oak panel, 90 x 164 cm. Dijon, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv. CA 134 © Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon/François Jay

In the Woods of Blainville

Marcel Duchamp was born in Blainville (Normandy). The surrounding landscape was the subject of his first forays into painting. ‘Painting has been declared dead for as long as I have painted. At some time I thought: You have reached a form where you can see it all from the funny side. And that is why I depicted Duchamp as a libertine, which he can be, absolutely.’ This painting has the lightness of the drawing pen: evidence that Baselitz can always and at any time find novel, spirited pictures. Painting is alive!

Georg Baselitz, In the Woods of Blainville, 2000, Oil on canvas, 250 × 200 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Newly in Love – M. D.

In the title, Baselitz uses the initials ‘M. D.’ to refer to Marcel Duchamp. Like in the other pictures on this wall, the depiction of the sex act with a female nude makes a glaring reference to Duchamp’s intermittently rampant love life. Baselitz sees him as an opponent. Duchamp had – and this was obviously entirely unacceptable for Baselitz – declared painting obsolete and became one of the founders of Minimal Art with his Readymades. With his paintings, Baselitz condemns him to living on within a medium he had declared dead.

Georg Baselitz, Newly in Love – M. D., 1999, Oil on canvas, 250 × 200 cm, Künzelsau. Museum Würth © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Lothar Schnepf, Cologne.

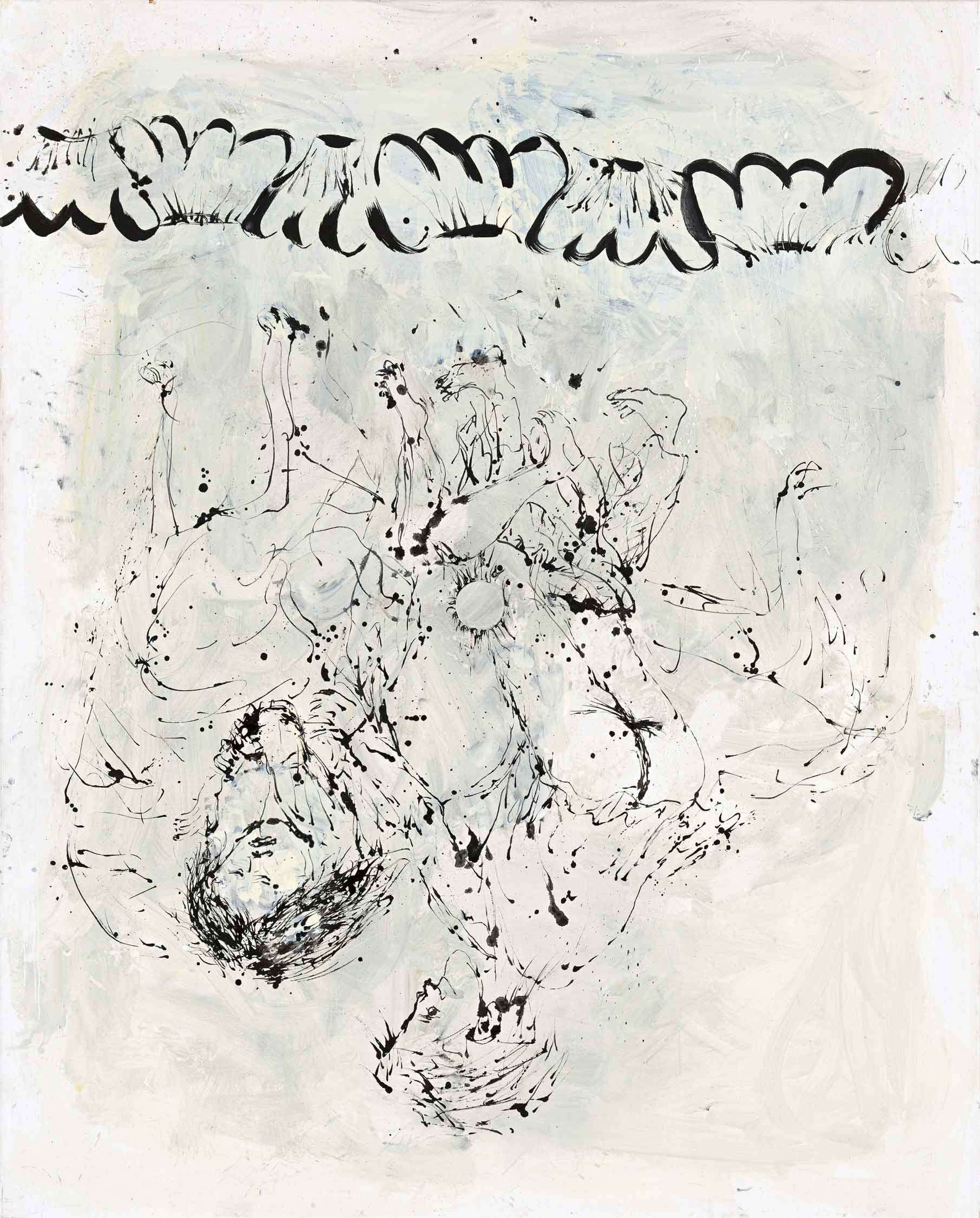

Band of Clouds

The pictures on this wall and the wall opposite have an extraordinary lightness, like oversized pen drawings or watercolours; as if they were floating, almost weightlessly. In the flutter of lines, we see a couple making love, at the centre of the picture is a circular hole. What’s behind the picture? The Rococo furniture on which the two are seeking their pleasure indicates that Baselitz took the composition from French prints that used to illustrate permissive erotic novels in the late 18th century.

Georg Baselitz, Band of Clouds, 2000, Oil on canvas, 250 × 200 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Melody

The male protagonist’s type and physiognomy indicate that this is Marcel Duchamp. For the composition of the group, Baselitz used ‘these erotic lithographs that are just inane.’ All the paintings of this light, fresh, and briskly painted group of works have a hole at their very center that was left by a paint tin placed there during the act of painting. ‘A hole in the picture allows the imagination to circle, as with the hole in a record, around which the music plays.’

Georg Baselitz, Melody, 1999, Oil on canvas, 250 × 200 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

In the Woods of Blainville

Marcel Duchamp was born in Blainville (Normandy). The surrounding landscape was the subject of his first forays into painting. ‘Painting has been declared dead for as long as I have painted. At some time I thought: You have reached a form where you can see it all from the funny side. And that is why I depicted Duchamp as a libertine, which he can be, absolutely.’ This painting has the lightness of the drawing pen: evidence that Baselitz can always and at any time find novel, spirited pictures. Painting is alive!

Georg Baselitz, In the Woods of Blainville, 2000, Oil on canvas, 250 × 200 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Newly in Love – M. D.

In the title, Baselitz uses the initials ‘M. D.’ to refer to Marcel Duchamp. Like in the other pictures on this wall, the depiction of the sex act with a female nude makes a glaring reference to Duchamp’s intermittently rampant love life. Baselitz sees him as an opponent. Duchamp had – and this was obviously entirely unacceptable for Baselitz – declared painting obsolete and became one of the founders of Minimal Art with his Readymades. With his paintings, Baselitz condemns him to living on within a medium he had declared dead.

Georg Baselitz, Newly in Love – M. D., 1999, Oil on canvas, 250 × 200 cm, Künzelsau. Museum Würth © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Lothar Schnepf, Cologne.

Band of Clouds

The pictures on this wall and the wall opposite have an extraordinary lightness, like oversized pen drawings or watercolours; as if they were floating, almost weightlessly. In the flutter of lines, we see a couple making love, at the centre of the picture is a circular hole. What’s behind the picture? The Rococo furniture on which the two are seeking their pleasure indicates that Baselitz took the composition from French prints that used to illustrate permissive erotic novels in the late 18th century.

Georg Baselitz, Band of Clouds, 2000, Oil on canvas, 250 × 200 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Melody

The male protagonist’s type and physiognomy indicate that this is Marcel Duchamp. For the composition of the group, Baselitz used ‘these erotic lithographs that are just inane.’ All the paintings of this light, fresh, and briskly painted group of works have a hole at their very center that was left by a paint tin placed there during the act of painting. ‘A hole in the picture allows the imagination to circle, as with the hole in a record, around which the music plays.’

Georg Baselitz, Melody, 1999, Oil on canvas, 250 × 200 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

‘That’s what it could look like in the future.’

David & Bathseba

David is engulfed by his passion for Bathsheba, his captain Uriah’s wife. The clever, asymmetrical structure with the light female figure, the reflection of her face in the mirror and the King’s menacing, desirous gaze recounts the beginning of an abysmal story. The vermilion sheen signals danger. The painting’s color and complicated interplay of glances aroused Baselitz’s interest. Also, not least, the asymmetry that he had created in his picture Milioninver, too – by the layer of white added at the very end.

Hans von Aachen, David and Bathsheba, 1612/15, Canvas, 138 × 105 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 1094

Milioninver

The wordplay of this title (in vermilion) gives voice to the song and dance, the silliness, the mischief that is idiomatically associated with the dragon’s blood of the colours. The painting has a special history: Baselitz initially structured the dark ground with the triplicate, slightly varied, very light figure of his wife, seated and nude apart from the high-heeled shoes. He then put the painting aside for a few years and eventually covered it with its bright, gestural layer of vermilion. And thought: ‘that’s what it could look like in the future.’

Georg Baselitz, Milioninver, 2010-13, Oil on canvas, 260 × 304 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

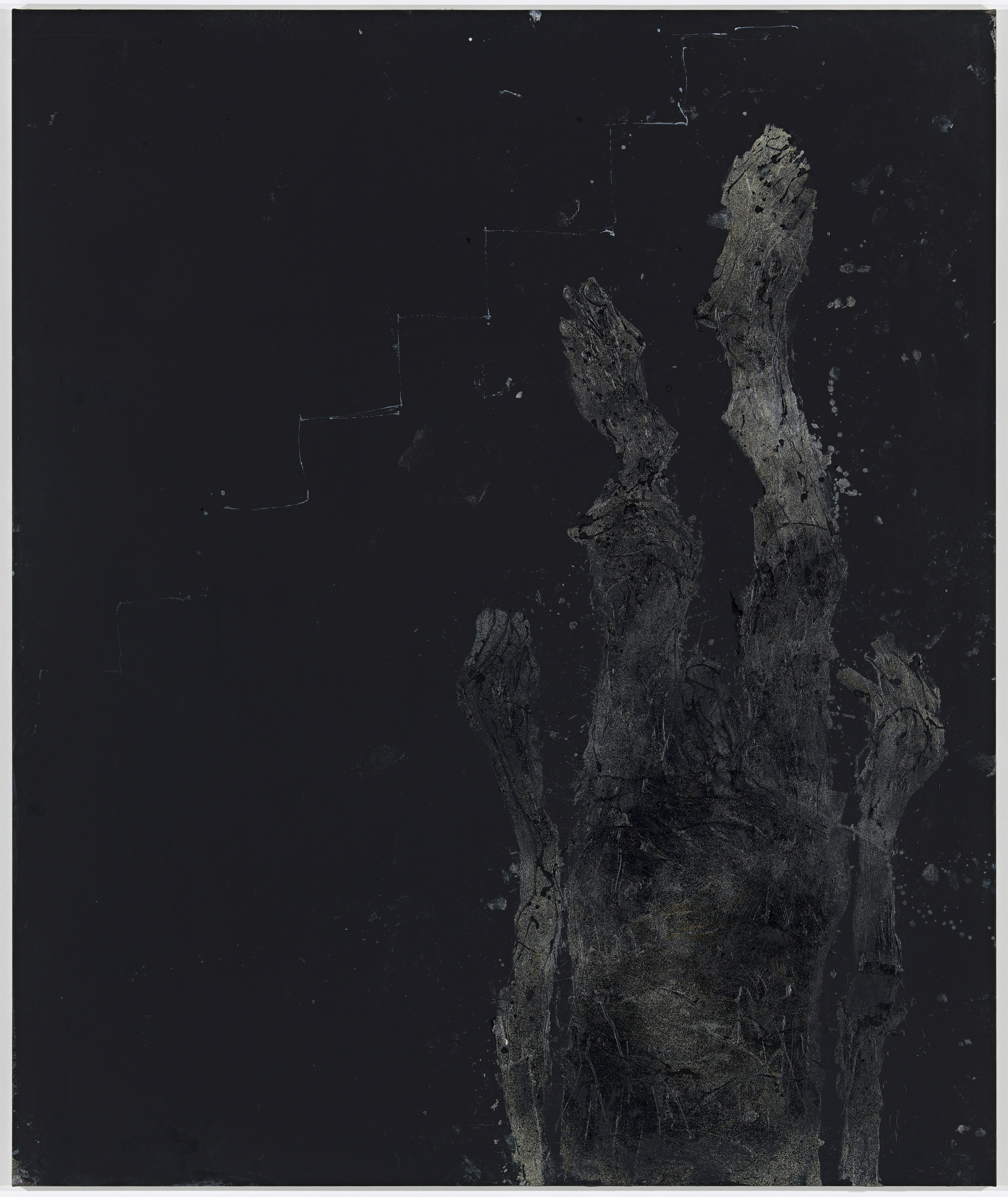

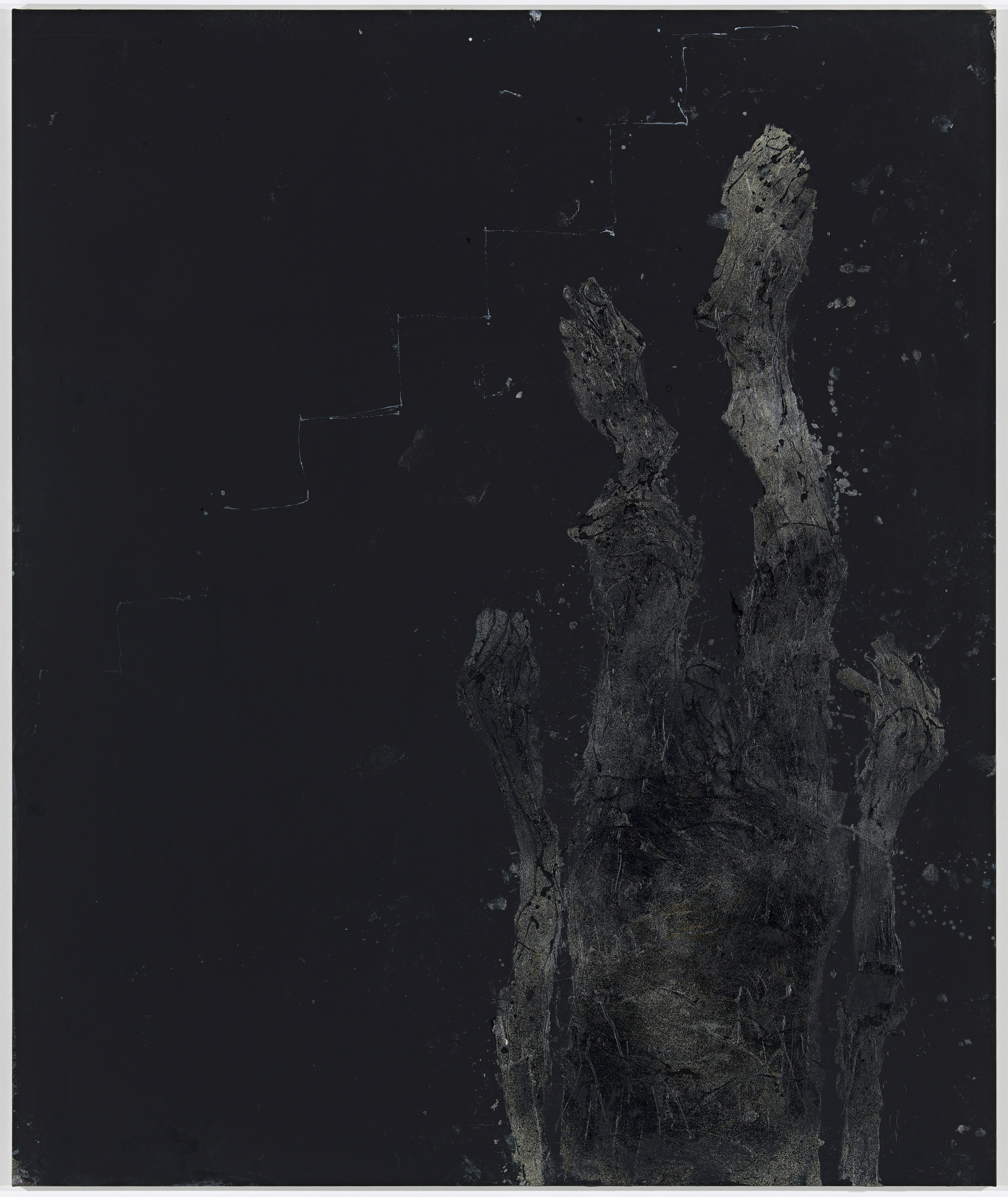

Where To

‘Where To’: it’s not a question, it’s a statement. The pale, fragile figures of the artist and his wife – are they emerging from the dark ground of sprayed color mists or are they submerging within them? Appearing or disappearing? Rising or falling? The essence is in limbo. The stream of pictures alters appearance, painting will not cease.

Georg Baselitz, Where To, 2017, Oil on canvas, 305 × 240 cm. Munich, Wittelsbacher Ausgleichsfonds © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

‘You come back, wavering shapes, out of the past / In which you first appeared to clouded eyes.

Should I attempt this time to hold you fast? / Does this old dream still thrill a heart so wise?’

Goethe

Nymph & Shepherd

Titian created this masterpiece when he was about eighty years old. In contrast to his earlier mythologies, it is not possible here to identify a particular textual source. It seems Titian did not want to ‘illustrate’ an existing narrative, but wanted to ‘write poetry’ out of his own right as a pictorial artist. The music fades out and in all her proximity, the nymph remains apart from the shepherd. Her gaze is on us. In its open, restless style of painting, the picture is about Eros as memory, as utopia.

Titian, Nymph and Shepherd, 1570/75, Canvas, 149.6 × 187 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 1825

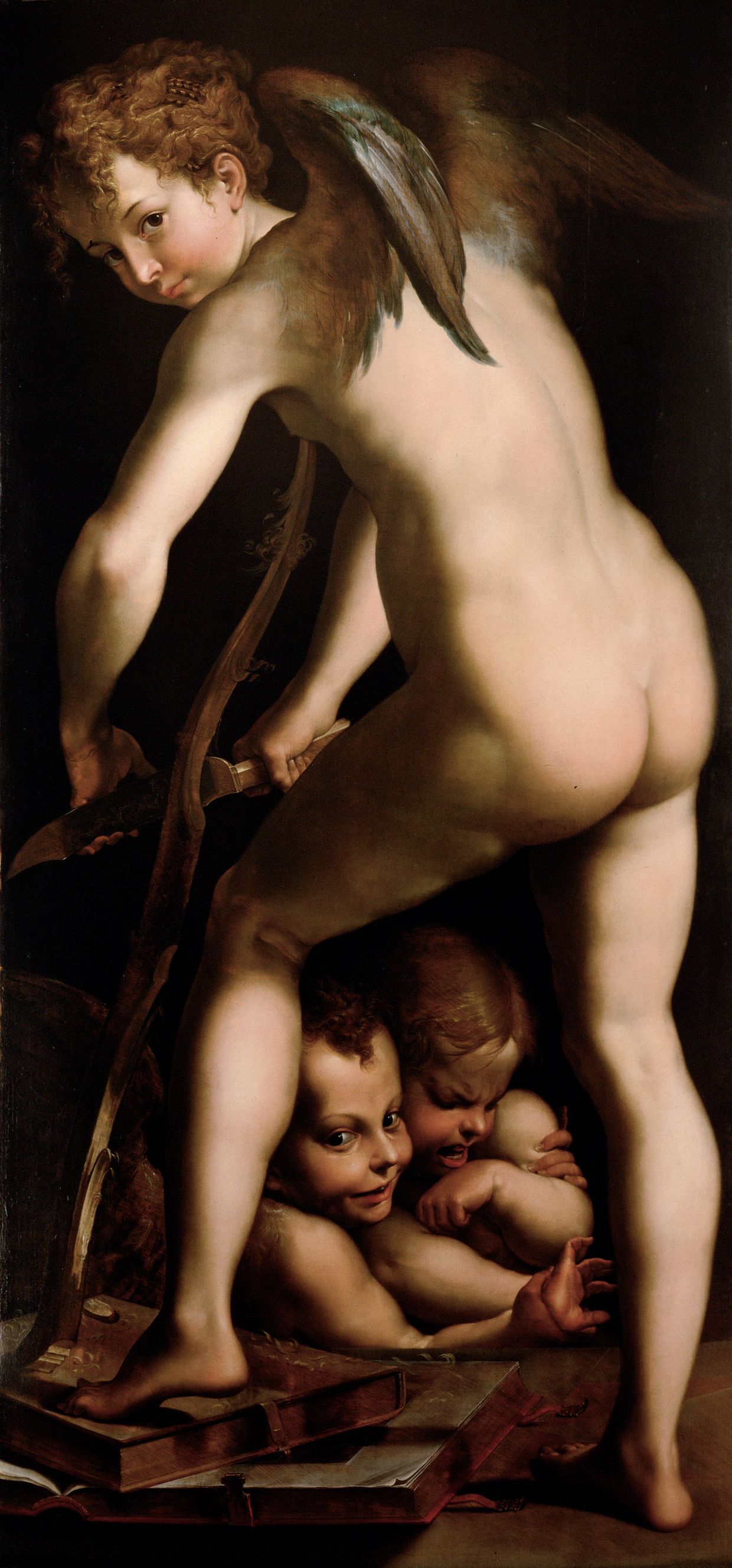

Bogenschnitzender Amor

A duplicate Amor is Baselitz’s answer to the couples in this group of pictures that are about pairing (in many senses of the word). They are about Eros, about desire, but also about the existence as a couple and the fragile unit of the twosome. And first and foremost, they are about the Eros of pictures, which Emperor Rudolph had succumbed to so much that he had this copy made although he also owned the original. A closer look is as rewarding here as it is for the subtly nuanced variants within which Baselitz keeps expanding on and altering his pictorial inventions.

(Left) Joseph Heintz the Elder, Cupid Making His Bow, after 1603, Wood panel, 135 × 64 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 1588

(Right) Francesco Mazzola, called Parmigianino, Cupid Making His Bow, 1534/39 Lime panel 135.5 × 65 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 275

Descending with Marcel

It is his own, fragmented nude body that Baselitz depicts here. The legs indicate strides and the extremely fine line of white steps over the feet marks a staircase. In combination with the title, the reference to Duchamp’s famous painting Nude Descending a Staircase (1912, Philadelphia) is apparent: a work that is for all intents and purposes the iconic marker of the departure from the picture, from painting. Baselitz revises this step, unacceptable to him, by incorporating the motif and thereby refuting Duchamp in painting.

Georg Baselitz, Descending with Marcel, 2016, Oil on canvas, 307 × 257 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Dear Marcel Duchamp, You Stole That from Picasso!

The title sounds humorous, but Baselitz takes the matter very seriously: ‘Processing through an opponent’ is what he says about his conflict with Duchamp. Baselitz occupies the other’s pictorial motif and develops it by painterly means in order to demonstrate that painting cannot be destroyed. Triple appearance in full figure. The glow of the feet suggests the painter approaching from spatial and temporal depths. It is as if a picture like this provided irrevocable evidence for a claim to eternity that painting has had since mythical prehistoric times.

Georg Baselitz, Dear Marcel Duchamp, You Stole That from Picasso!, 2016, Oil on canvas, 410 × 305 cm. Private collection. © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Like It Was Before

Time passes, as Baselitz indicates in his title. In this picture, the painter picks up on his depictions of the seated nude Elke from 1976 – four decades! In the larger format, the strong colouration of the original is now extremely reduced. The grey shades of the figure are mixed with Indian yellow. A strange, sallow light is emitted. Is the figure in the picture appearing or about to disappear? Whence or whereto? Fundamentals are in limbo. Fragility and monumentality enter a precarious union.

Georg Baselitz, Like It Was Before, 2016, Oil on canvas, 300 × 250 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Descending with Marcel

It is his own, fragmented nude body that Baselitz depicts here. The legs indicate strides and the extremely fine line of white steps over the feet marks a staircase. In combination with the title, the reference to Duchamp’s famous painting Nude Descending a Staircase (1912, Philadelphia) is apparent: a work that is for all intents and purposes the iconic marker of the departure from the picture, from painting. Baselitz revises this step, unacceptable to him, by incorporating the motif and thereby refuting Duchamp in painting.

Georg Baselitz, Descending with Marcel, 2016, Oil on canvas, 307 × 257 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Dear Marcel Duchamp, You Stole That from Picasso!

The title sounds humorous, but Baselitz takes the matter very seriously: ‘Processing through an opponent’ is what he says about his conflict with Duchamp. Baselitz occupies the other’s pictorial motif and develops it by painterly means in order to demonstrate that painting cannot be destroyed. Triple appearance in full figure. The glow of the feet suggests the painter approaching from spatial and temporal depths. It is as if a picture like this provided irrevocable evidence for a claim to eternity that painting has had since mythical prehistoric times.

Georg Baselitz, Dear Marcel Duchamp, You Stole That from Picasso!, 2016, Oil on canvas, 410 × 305 cm. Private collection. © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Like It Was Before

Time passes, as Baselitz indicates in his title. In this picture, the painter picks up on his depictions of the seated nude Elke from 1976 – four decades! In the larger format, the strong colouration of the original is now extremely reduced. The grey shades of the figure are mixed with Indian yellow. A strange, sallow light is emitted. Is the figure in the picture appearing or about to disappear? Whence or whereto? Fundamentals are in limbo. Fragility and monumentality enter a precarious union.

Georg Baselitz, Like It Was Before, 2016, Oil on canvas, 300 × 250 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Cain’s Fratricide

The parents’ fall from grace is followed by the offspring’s fratricide in biblical logic. It is a primal scene in the history of humankind that touches our lives until this day. Cain’s burnt offering is blazing in the background like the hellfire into which Orpheus descended. Manfredi’s picture follows an almost physical logic: the bodies of the two young men are aggressively interlocked, the extremities stretched out in all directions speak of fear, hatred and brute force.

Bartolomeo Manfredi, Cain’s Fratricide, c.1615, Canvas, 152 × 115 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 363

Displaced Persons

The extreme is shown through extremities here. The tragical goes hand in hand with the grotesque, as the couple is wearing nylon stockings glued into the picture on their arms. There are seven stockings, because even in the extremes of existential loss, the two are inseparably intertwined.

"Displaced Person" (DP) has since 1943 been the official term for people unable to return to their homes and loved ones due to war.

Georg Baselitz, Displaced Persons, 2020, Oil, dispersion adhesive, and nylon stockings on canvas, 295 × 310 cm. Courtesy Gagosian © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Orpheus & Eurydice

The mythical singer Orpheus fails to liberate his beloved wife Eurydice from the Netherworld after she dies from a snakebite. He conquers the Gods by his art, music, but he is unable to fulfil their condition not to look at his beloved. Love, yearning, and longing to see lead the couple to become aware of themselves as Displaced Persons as they lose each other.

Giovanni Antonio Burrini, Orpheus and Eurydice, 1695/1705, Canvas, 120 × 119.5 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 5762

Nylon Parade

Since the spring of 2020, a new, surprising element has entered Baselitz's pictorial world - he inserts nylon stockings into his paintings now. Baselitz was inspired by Dada artist Kurt Schwitters and Hannah Höch's photomontages.

Nylon stockings were fetishized in the postwar period and also played an important role in film, for example, Sophia Loren in the film "Ieri, oggi e domani" by Vittorio De Sica (1963), a director Baselitz greatly values.

Georg Baselitz, Nylon Parade, 2022, Oil, dispersion adhesive, and nylon stockings on canvas, 300 × 400 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Saint Jerome

To forego physical temptations was one of the central teachings of Jerome (347–420). ‘Chastity that attests to purity of the mind more than that of the body’ was not only a monk's ideal for Jerome, but meant to govern the way men and women lived together. Here, he is depicted listening to the trumpet of the Last Judgement as he translates the Holy Scripture. His extremities stretch out in ecstasy before the dark background and correspond grotesquely to the nylon stocking in the above picture.

Guido Cagnacci, Saint Jerome, after 1659, Canvas, 160 × 110.5 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 1665

‘How are pictures made? Are they still possible or not?

Do you apply something, glue something on, draw spots, wipe, or walk to China?’

The Last Judgement

Even a century before Frans Floris, painters like Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Hans Memling had the damned plunge into hell head over feet at the Last Judgement – but always great numbers of small figures. Floris monumentally brings the motif to the fore in a single figure that is intended to inspire us to a devout life by its horror.

Frans Floris, The Last Judgement, 1565, Canvas, 162 × 220 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 3581

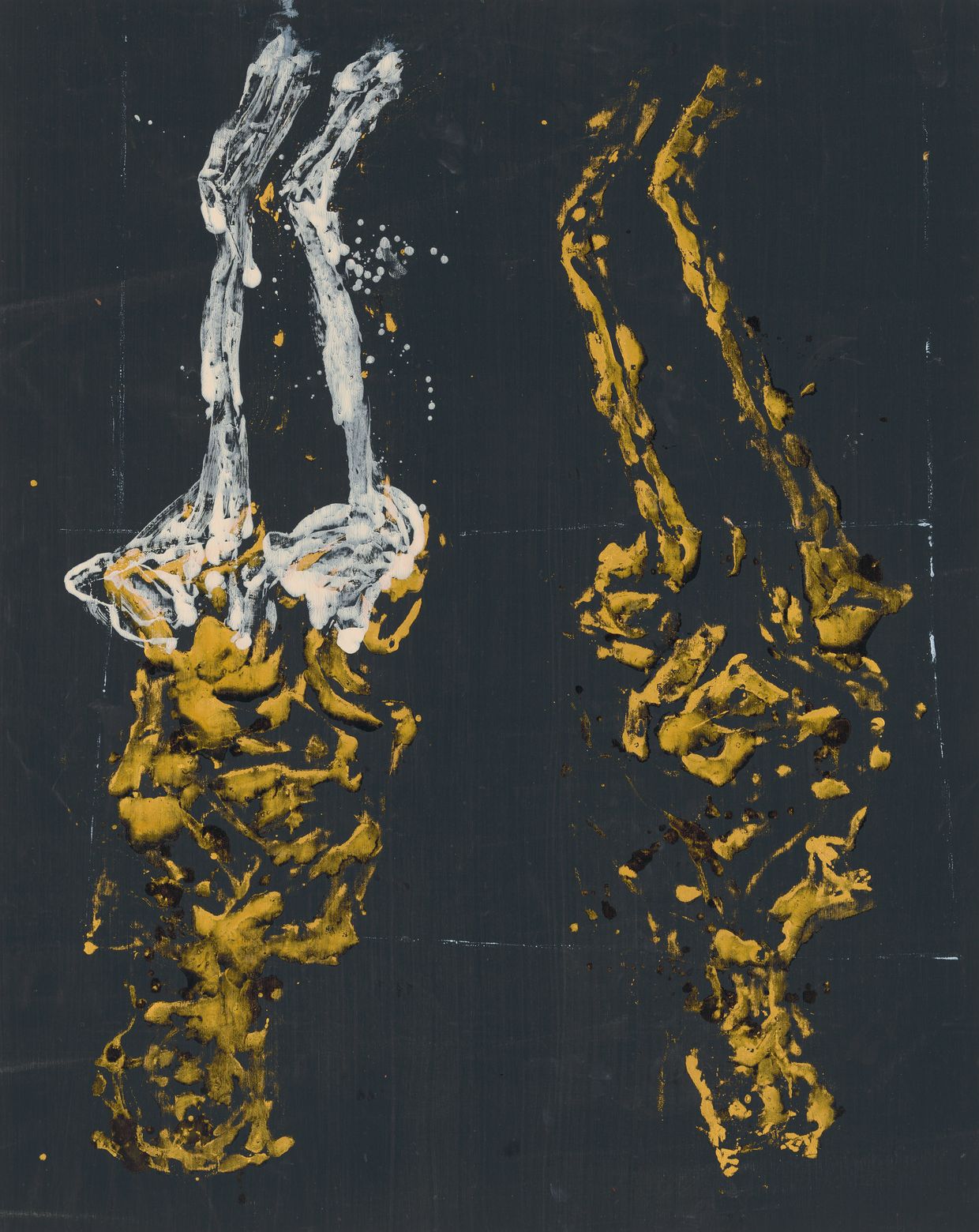

Menu militare

The shadowy appearance to the two golden figures is saved from sinking into the black ground by the artist’s striking placement of colour: the legs of the figure on the left are in an abrupt white that enhances their presence. The ceremonial triad of colour leaves the motif unclear: there’s only the finest insinuation of a bench, and it is also impossible to say who it is who is appearing here.

The couple or the duplicate Elke?

The title implies scarcity, scantness, privation.

Georg Baselitz, Menu militare, 2021, Oil and painter’s gold varnish on canvas, 250 × 200 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

The Ice Skating Woman

The canvas as an arena in which to act: this is how the critic Harold Rosenberg described the approach of American Action Painting in 1952. Here, Baselitz confidently plays with the method, but does not quite relinquish the object as the title shows.

The ‘ice skating woman’, however, is not even an ice skater, but a recourse to a seated Elke from 1974. We are not looking at an ice skater floating across the lake at all; instead, our entire vision begins to float as we consign ourselves to the free structure of the picture.

Georg Baselitz, The Ice Skating Woman, 2019, Oil on canvas, 250 × 200 cm. Private collection © Georg Baselitz 2023, photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

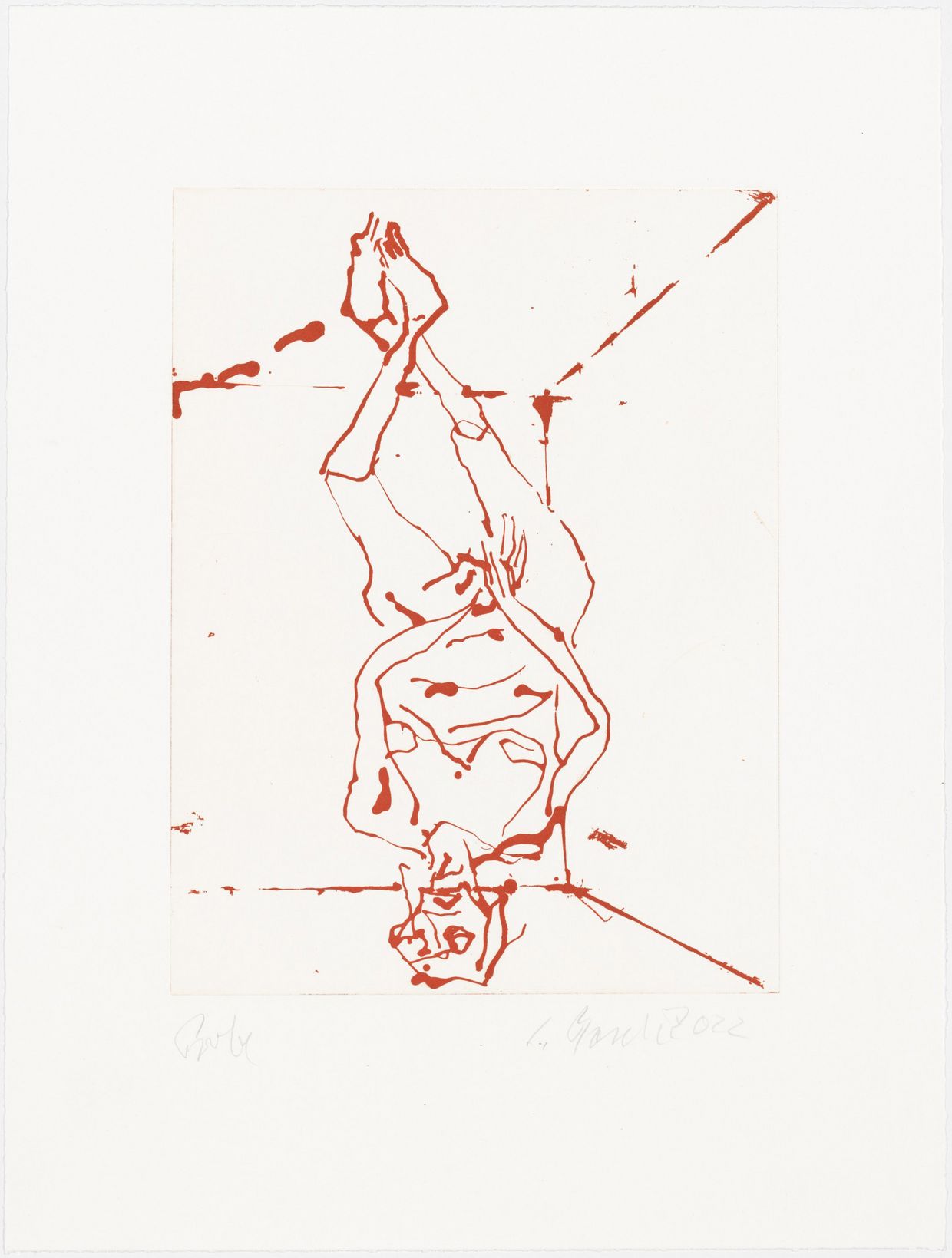

ARTIST EDITION EXCLUSIVELY FOR THE KUNSTHISTORISCHE MUSEUM WIEN

SPIELT DIE MUSIK

Georg Baselitz • 2022

Limited Edition of 100 (50 red/50 black) + 10 (5 red/5 black) Artist Proofs; numbered and signed

Technique: line etching

Paper: Somerset

Printing Plate: 33.4 cm x 25 cm; Sheet Size: ca. 52 cm x 39 cm

Print: Mette Ulstrup bei Niels Borch Jensen, Kopenhagen

© Georg Baselitz 2023. Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Buy

Sold out

Introduction video in sign language